Blood flow is essential in maintaining tissue health, especially following an injury, as it provides the vital reparative factors necessary for healing. Compromised blood flow then, can significantly inhibit tissue healing. In regards to the feet, the posterior tibial artery of the lower leg supplies blood to the plantar region (bottom, sole) of the foot, including the plantar fascia via the lateral plantar artery.

Plantar fasciitis, a highly prevalent injury and one of the most common causes of plantar heel pain, remains poorly understood in conventional podiatry. However, as Dr. Harvey Lemont, DPM, et al., found in their 2003 research study reviewing histological findings in chronic plantar fasciitis cases, plantar fasciitis is significantly more often accompanied by degenerative changes rather than active inflammation. Thus, these degenerative changes in the fascia are best classified as a “fasciosis” rather than fasciitis. While degeneration and inflammation are not mutually exclusive, it is typical for podiatrists to treat PF as inflammation.

So, what about the degenerative processes then?

Given the importance of blood flow in tissue healing, quality of blood flow may help explain the 46% recurrence rate of plantar fasciitis reported in previous research. An adducted hallux (when the big toe is displaced towards the other toes, such as a bunion), which is seen within narrow footwear with tapered toe boxes, can put passive tension on the abductor hallucis muscle (which attaches to the big toe and the heel bone along the medial aspect of the foot), compressing the lateral plantar artery and restricting blood flow to the plantar fascia.

A recent study by Jacobs, et al. from 2019 published in the Journal of Foot and Ankle Research used ultrasound to compare lateral plantar artery blood flow before and after passive hallux adduction. The lateral plantar artery was imaged deep to the abductor hallucis for 120 seconds; 60 seconds at rest, then 60 seconds of passive hallux adduction. The volume of blood flow was 22.2% lower after passive hallux adduction compared to before, with an initial drop of about 60%. Blood flow was also compared with arch height, and as arch height decreased, there was a greater negative change in blood flow, meaning individuals with lower arch height appear to have a greater risk of decreased blood flow with passive hallux adduction. These findings of decreased blood flow through passive hallux adduction indicate conditions that elicit passive hallux adduction (e.g. wearing narrow-toed shoes) may have important effects on foot blood flow. Many shoes also simultaneously compress the foot in multiple directions, which may influence overall blood flow in the foot and reduce the potential for compensatory increased blood flow in collateral arteries. A decrease in blood flow, due to footwear or otherwise, could have a negative impact on tissue health and healing as has been seen with the Achilles tendon, scaphoid, and patella.

So, how do I restore optimal blood flow to my plantar fascia?

First, we remove the obstacles to cure: stop wearing narrow shoes with tapered toe boxes. Eliminate the force that deviates the big toe laterally towards the other toes. Instead, wear more natural footwear with a toe box widest at the ends of the toes that accommodates a full, natural toe splay. See our list of Correct Toes Approved shoes for suggested options.

Second, try a toe spacing orthotic like Correct Toes to help rehab and restore your toes to their natural and anatomically correct alignment—a wide splay. Getting the big toe back to its natural alignment with the first metatarsal bone will take tension off of the abductor hallucis muscle, reducing its compression on the lateral plantar artery and increasing blood flow. Wearing Correct Toes while weight-bearing and active will yield quicker and longer lasting results as the intrinsic foot muscles are encouraged to engage and strengthen in a healthy alignment.

Additionally, there are several exercises one can do to help facilitate this process. Some successful strategies include pulling the big toe back over medially by hand, tractioning the big toe (pulling distally away from the foot), and massaging the abductor hallucis muscles, which lies between the first and second metatarsal. See our Bunion Stretch and Soft Tissue Release video for a demonstration. Performing the Toe Extensor Stretch will also help to lengthen the muscles and tendons on dorsum (top) of the foot while simultaneously reducing tension on the plantar fascia. This stretch is particularly effective for counteracting the injurious tendencies resulting heel elevation and toe spring, which chronically overstretch the plantar fascia.

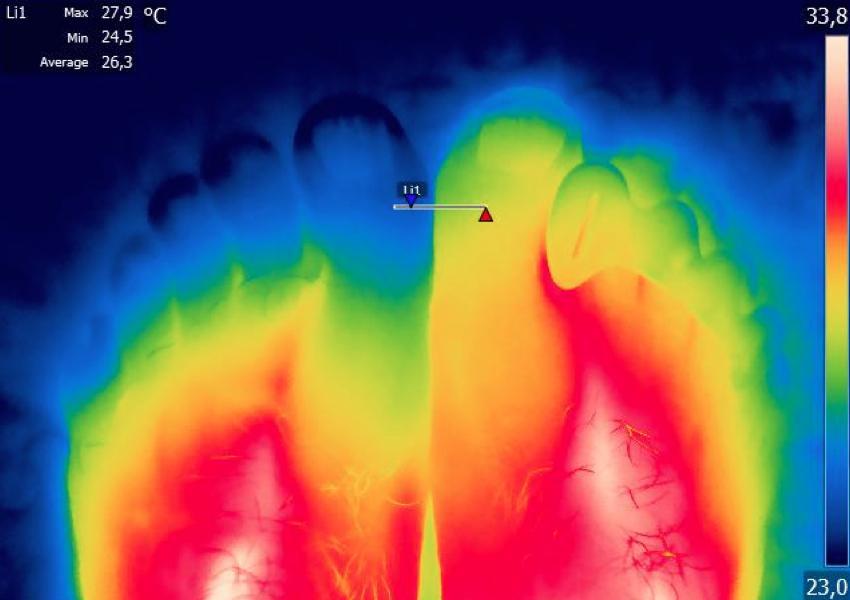

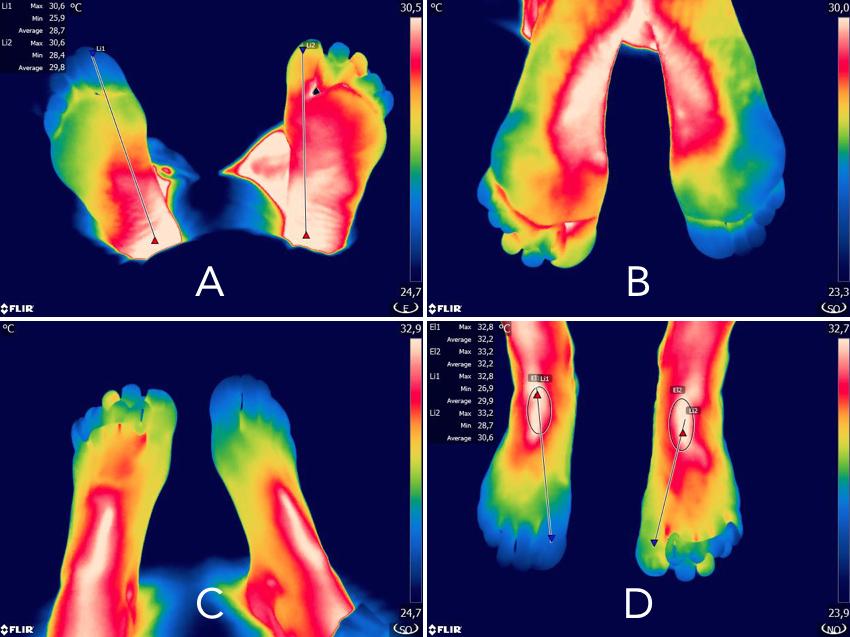

The image above depicts the difference between foot temperature and blood flow, comparing a foot wearing Correct Toes (left foot) to a foot without Correct Toes on (right foot). As a reminder, the study initially mentioned above by Jacobs, et al. compared a foot without Correct Toes on to a foot with a passively adducted hallux (as a representation of the big toe position within narrow, tapered toe boxes). Thus, we can justly surmise that the difference in blood flow between a foot with Correct Toes on compared to a foot with a passively adducted hallux will be even greater. As one might imagine, restoring and improving blood flow to the feet will not only help with foot health, but can also impact the, heart, brain, and cardiovascular system as a whole.

Blood flow is a two-way street, what about venous return to the heart?

This leads us to blood return and the venous system. Once nutrient-dense, oxygenated blood travels (with the help of gravity) all the way down to the tips of our toes, it often needs a little extra assistance to bring the deoxygenated blood back up (against gravity) to the heart. The body accomplishes this by way of musculo-venous pumps. The two major venous pumps in the lower extremities are found within the central plantar aspects of the feet and within the calf muscles.

In the foot, the plantar venous plexus pump initiates venous return. This occurs each time you take a step, as your medial longitudinal arch stretches and pronates, followed by contraction and flexion. While at rest (or when walking, between step propulsion and when the heel touches down) blood is pooled in the foot veins. When the front of your foot touches down and your arch pronates, that pooled blood is squeezed and discharged upwards by the foot musculature. After surgery, mechanically inflating balloon pumps use this mechanism to prevent pulmonary embolism (PE) and deep venous thrombosis (DVT) when patients are immobilized post-operation.

- This healthy and natural pronation during gait is essential for the plantar venous plexus to pump optimally. The intrinsic foot muscles and arches need to be mobile and flexible, yet strong enough to pump blood back up into the calf muscles. Rigid shoes with arch support don’t allow for this kind of flexibility and movement, restricting the foot’s ability to pump during locomotion. An artificial arch support will also prevent the ability of the foot arch to naturally pronate while walking as well as provide an unnecessary compressive force while the foot vasculature should be filling and blood pooling.

The discharged blood from the foot will then enter veins in the soleus muscle. This muscle extends from the ankle to the back of the knee and contains critical veins responsible for passing oxygen-depleted blood through the lower legs up through the knee, which serves as a branching point for vasculature in the lower leg. Each time this calf muscle contracts, it applies pressure to the veins; that pressure is what fuels venous return. The calf muscle is known as the “secondary heart” by vein specialists and medical professionals.

- For calf muscles to function optimally, the heel and forefoot need to be the same distance from the standing surface, as they are when barefoot and how nature intended. Shoes with heel elevation rob our calf muscles of their pumping and performance potential by preventing full extension of the calf, chronically shortening and stiffening the Achilles tendon and associated muscles of the lower leg. A 2010 study by Csapo, et al., found that long-term use of high heels induces shortening of the gastrocnemius muscle by 13% and increases Achilles tendon stiffness by 22%, while also reducing the ankle’s active range of motion.

A common sequelae of chronically weakened calf muscles is varicose veins. Without the ability to efficiently pump deoxygenated blood back (against gravity) to the heart, blood begins to excessively pool in the feet and lower legs, causing the vein walls to loosen and dilate, resulting in varicose veins. There are many procedures, and botanical and topical treatments that can help with varicose veins, but the natural way to prevent them is be active and mobile while avoiding rigid, tight shoes with unnecessary heel elevation and arch support, and seek natural, foot-shaped shoes that are flat and flexible, allowing for full toe splay.

Sources

- 1. Plantar Fasciitis: A Degenerative Process (Fasciosis) Without Inflammation. Lemont, et al. Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association (2003) 93:3 234-237.

- PMID: 1275631 | DOI: 10.7547/87507315-93-3-234

- 2. Passive hallux adduction decreases lateral plantar artery blood flow: a preliminary study of the potential influence of narrow toe box shoes. Jacobs, et al. Journal of Foot and Ankle Research (2019) 12:50.

- PMID: 31700547 | DOI: 10.1186/s13047-019-0361-y

- 3. On muscle, tendon and high heels. Csapo, et al. Journal of Experimental Biology (2010) 213:2582-2588.

- PMID: 20639419 | DOI: 10.1242/jeb.044271

Written by: Dr. Andrew Wojciechowski, ND

If you’re seeking more individualized foot health care and would like to work with Dr. Andrew directly, you can schedule at Northwest Foot and Ankle.

Schedule a virtual remote consultation with Dr. Andrew Wojciechowksi, ND.

Schedule an in-person appointment with Dr. Andrew Wojciechowski, ND at Northwest Foot & Ankle in Portland, OR.